|

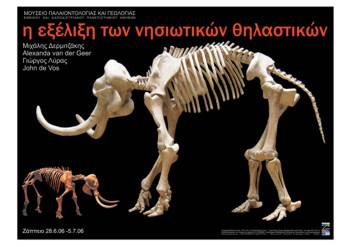

During the Plio-Pleistocene many islands of the World were inhabited by endemic mammals of mainland origin. Today, most of these island endemics are extinct and are known to us only by their fossil remains. The insular mammals present unique adaptations to the island environment compared to their mainland relatives, such as smaller size and robust and short limbs. I participate in the project Of Mice and Mammoths of Mark Lomolino, Dov Sax and Maria Rita Palombo by investigating the importance, degree and direction of body size changes in insular mammals.

One of the aims of the project was to test the generality of the so-called island rule. The database assembled thus far comprises 1593 populations of insular mammals (439 species, including 63 species of fossil mammals).We found that the body size index (body mass of the insular population relative to the mainland population) was significantly and negatively related to the mass of the ancestral or mainland population across all mammals and within all orders of extant mammals analysed, and across palaeo-insular (considered separately) mammals as well. Insular body size was significantly smaller for bats and insectivores than for the other orders studied, but significantly larger for mammals that utilized aquatic prey than for those restricted to terrestrial prey. Our main conclusions are that the island rule appears to be a pervasive pattern, exhibited by mammals from a broad range of orders, functional groups and time periods. There remains, however, much scatter about the general trend; this residual variation may be highly informative as it appears consistent with differences among species, islands and environmental characteristics hypothesized to influence body size evolution in general. The more pronounced gigantism and dwarfism of palaeo-insular mammals, in particular, is consistent with a hypothesis that emphasizes the importance of ecological interactions (time in isolation from mammalian predators and competitors was between a hundred thousand to a million years for palaeo-insular mammals, but less than ten thousand year for most extant populations of insular mammals. While ecological displacement may be a major force driving diversification in body size in high-diversity biotas, ecological release in species-poor biotas often results in the convergence of insular mammals on the size of intermediate but absent species.

|