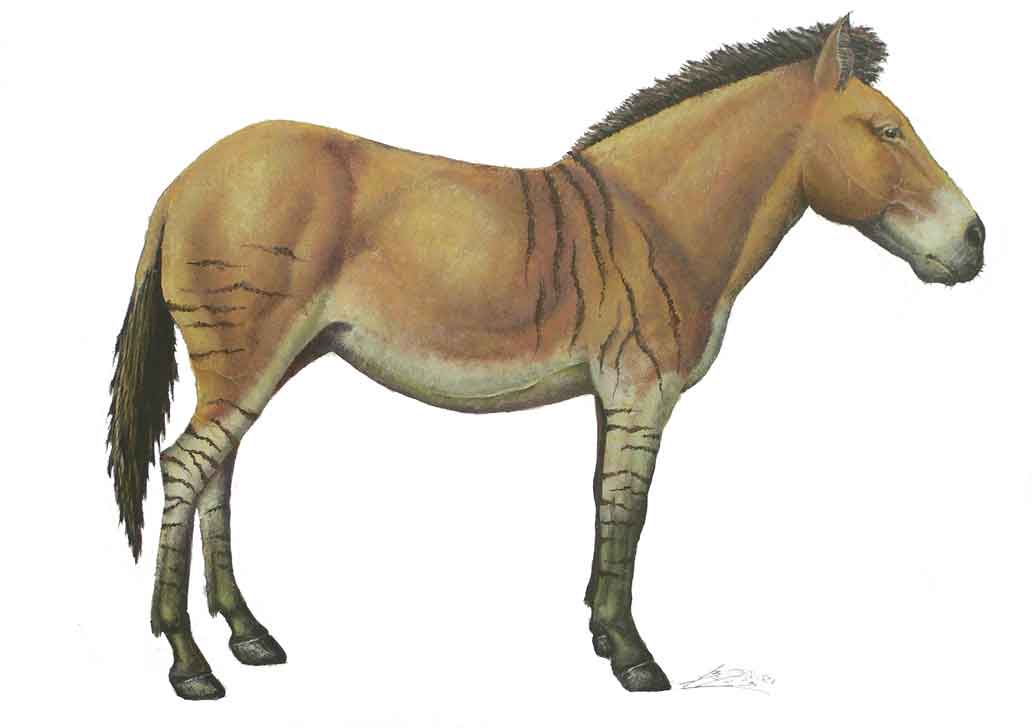

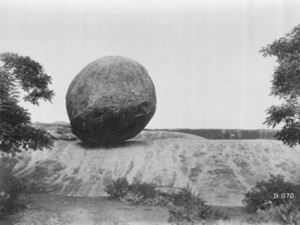

[Krishna's butterball at Mahabalipuram (Tamil Nadu); photograph Archaeological Survey of India, courtesy Kern Institute, Leiden (the Netherlands) ]

|

Geological phenomena in the landscape (eroded stones, mountains, giant steps, volcanoes) and fossils (petrified remains of life of the past) are often considered proofs of myths and legends. In Kathmandu valley (Nepal), plain stones represent the Matrikas (mother goddesses). They are attributed a soul, and are considered alive. More often, these stones (mani stones) are inscribed or adorned with a simple carving, e.g. of a lotus flower, and given to the mountain gods at chorten, small shrines or sometimes nothing more than a heap of such stones. Often these mani stones are lined up, and cross the landscape in the form of seemingly endless walls. Examples of eroded stones are Krishna’s butter ball near Mahabalipuram in Tamil Nadu, and a ring stone along the Sutlej river.

Ammonites, extinct carnivorous molluscs, are worshipped in India as symbols of the god Vishnu, based on their wheel-shaped form (chakra. There are many types of these so-called shalagramas, depending on the degree of preservation, color, shape etc. White fossil corals from Dvaraka, the submerged city of Krishna, also bear chakra markings, and are used as shalagrama. Evidence for nagas, a race of wise, mythical snakes, is found in the Himalayas, where fossil ammonites and fossil bones are abundantly found. These fossils are often pyritized or bearing calcite crystals, resembling sparkling jewels. Reports of naga palaces, shining with precious stones, may have been inspired by the spectacular Salt Range, where the sunlight is reflected by salt-crystals. Fossil sea urchins found in the Narmada Valley (Madhya Pradesh) are called five grooves (pancha khadda), obviously inspired by the five radiating ambulacral rays on the surface.

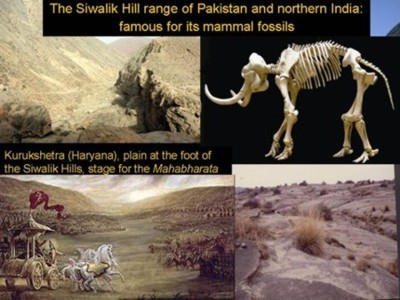

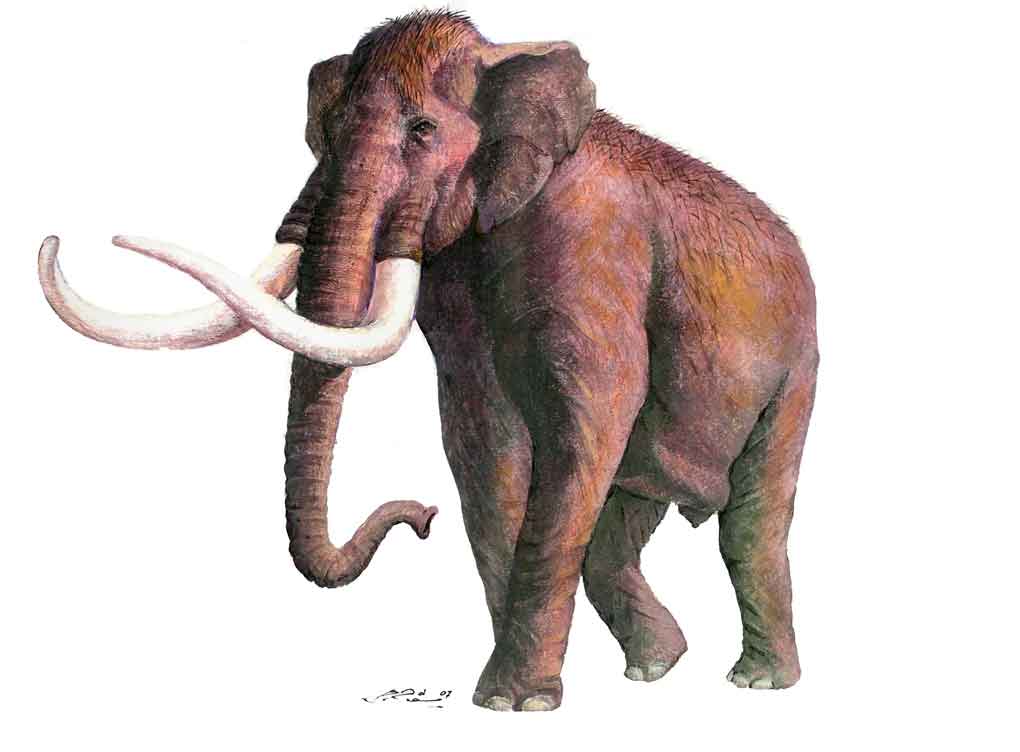

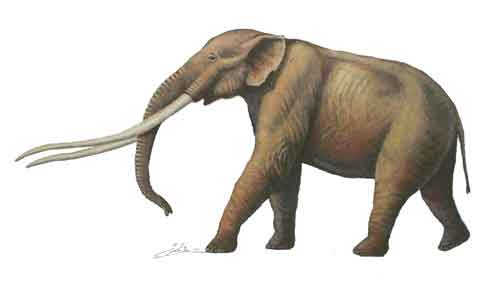

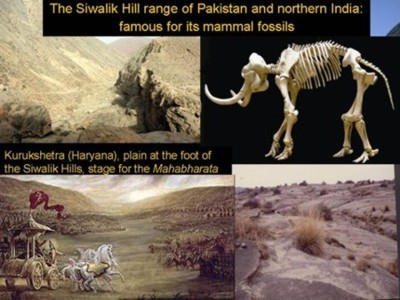

Abundant fossils are found on the surface in the Siwalik Hills, a range of Himalayan foothills, ranging from Pakistan to Myanmar. These fossils figure in local myths. In Pinjore Valley, they are remains of demonic rakshasas, killed by an epic hero. In the nearby former kingdom of Nahan, fossil elephant molars are considered heads of gods, obviously decapitated at some fight. Less than 50 kilometres away, the famous Kurukshetra plain was the stage for the epic battle as described in the Mahabharata. In my recent work on this subject, I make the link between the Pinjore and Nahan fossils, explained away as battle remains, and the battle of Kurukshetra. The plains of Kurukshetra are rich, too, in fossils, and more, archeological remains of Indus Valley settlements, such as Rakhigarhi, where ancient weaponry and pottery comes to the surface after rainfalls. The combined occurrence of bones and artifacts kept the memory of the battle alive.

Vishnu's chakra (disc) is represented by the shalagrama (ammonite) (from my ppt presentation at EASAS 2006)

Fossils are explained as epic battle remains in the Siwalik Hills (from my ppt presentation at EASAS 2006)

|